About Us

Language, Culture, and Communication

- July 14, 2020

- Posted by: Olga Werby

- Category: Articles on Teaching Supermarket Science Background

This article was originally published Interfaces.com.

Where we come from — our background culture: our country of origin and language, our heritage and religion (or lack there of), our family, our education, our friends, and where we live — has an enormous impact on our ability to communicate. What’s more, when people from different cultural backgrounds try to interact with each other, these differences can cause catastrophic failures.

Direct versus Indirect Communication Styles

Consider the following set of remarks about doing homework:

- Do your homework!

- Can you start doing your homework?

- Would you mind starting your homework now?

- Let’s clean the table so you can start your homework.

- Do you need help with homework?

- It’s getting late, do you have a lot of homework?

- Didn’t you say you have a lot of homework?

- Johnny’s mom said that he has a lot of homework today…

- Do you have everything ready for school tomorrow?

- Look how late it is — it’s almost time for bed. You have school tomorrow.

Each of the statements above represents a progressively less direct command to do homework. In my family, I usually pick number 2 to communicate my desires for finished homework to my sons (although number 1 is perfectly acceptable, to me). But depending on your (or your parents’) cultural background, the choice could be different in your family.

Number 10 is the least direct form of communication in this list, it hints at the desires of the speaker, requiring the listener to interpret the wishes. This requires a lot more attention to communicate information correctly, for both sides.

Some languages are better at a direct form of communication (as in Do your homework.). But some are more oblique by the very nature of the language. Consider languages that have the “vu” versus “tu” pronouns for the receiver of the command. Vu is reserved for situations where there are social power differences between the speaker and the listener: generational differences, social status differences, or polite speech. Tu is used between individuals with similar social status — friends, siblings, classmates — or when the listener is of a lower social standing. A boss might address a subordinate as a tu, but a subordinate might not feel comfortable saying tu to his boss. Thus languages like French, Spanish, and Russian embed indirectness into communication by their very grammar.

And even in an English speaking company, a subordinate might not feel comfortable saying something like: “Schedule the group meeting for tomorrow,” to his superiors. The more likely request would cascade down the directness scale depending on the culture of the company, the relative social standing between individuals, and degree of friendliness:

- Schedule the group meeting for tomorrow.

- Did you schedule the group meeting for tomorrow?

- Shouldn’t we schedule the group meeting for tomorrow?

- Don’t you think it’s a good idea to have a meeting tomorrow?

- It would be great if we could meet as a group to discuss this soon…

Sexual differences can also affect the degree of directness: “Would you like to stop for coffee?” “No.” We sometimes refer to these types of exchanges as passive-agressive. But the differences could easily be just due to preferred communication style.

As long as conversation sticks to meeting schedules, coffee, and homework, the amount of harm done when two individuals fail to communicate is not very high. But in other circumstances, when the stakes are higher — “Don’t you think your patient looks a little blue?” — the failure could be tragic.

Expressive versus Reserved Communication Style

Another difference in communication styles is due to amount of emotional expressiveness the speakers add to their verbal communication. Hand gesturing, exaggerated facial expressions, high variation on tone, choice of colorful language, all contribute to the degree of expressiveness.

If a person is not used to the accentuated conversation, the body gestures, changes in tone and voice, the differences in the delivery of various parts of the message can completely obscure the informational content. It’s easy to get lost when you don’t know what to focus on. And so the degree of expressiveness is yet another dimension that can divide speakers in a conversation.

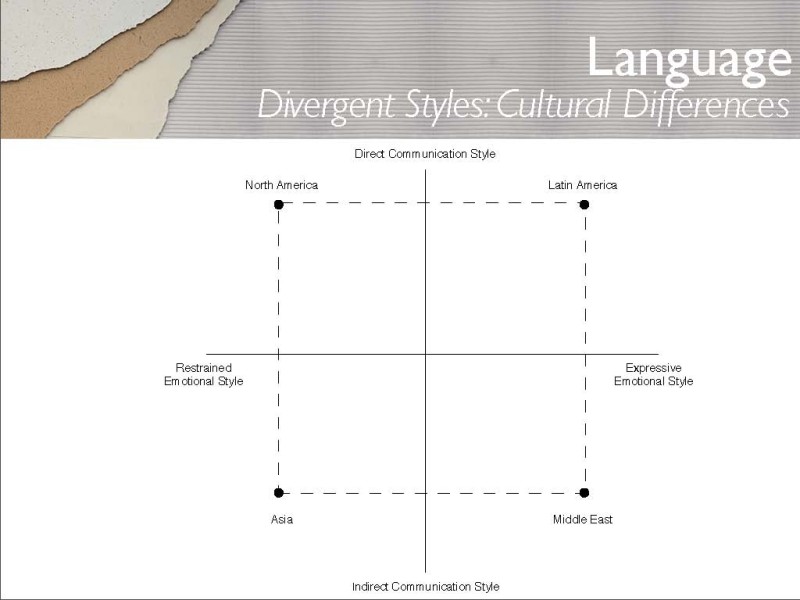

Below is a quick reference for the cultural differences in communication styles around the world. Of course it is only the grosses of approximations, but it should give a sense that cultural differences can change the intended meaning of communication.

All of the above differences in communication styles presume that the individuals involved in a conversation have a language in common and are speaking on a subject matter that both sides are equally familiar with. If not, communication can breakdown for more reasons than failure to find compatible communication styles.