About Us

6 Things to Think About When Forming an Educational Family Co-op

- July 18, 2020

- Posted by: Olga Werby

- Category: Supermarket Science Background

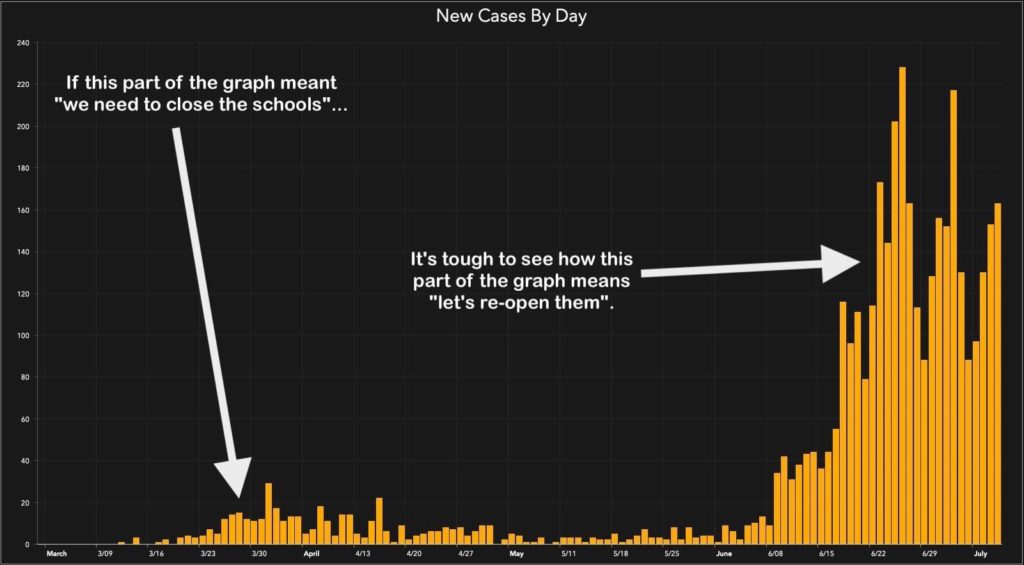

Some of the largest school districts have opted out of in-classroom education this fall. Given record infection numbers and death rates, it is the safest decision for families, teachers, and kids. For older children — those in high school and college — online education is a real option. Older kids have hopefully learned how to learn by the time they started ninth grade. Older kids can be left unattended at home for the duration of the school day (there are laws that prohibit kids younger than twelve-years-old to be left home alone, unsupervised). We all hope that these teenagers can take on the responsibility for their own education and understand the ramifications of not doing so to themselves and their families. But younger kids? Here is where the most difficulty arises. Not only younger children can’t be left alone at home, but they also can’t take over their own education management. This job falls on parents; and that’s a full-time job, as any parent or teacher will tell you. So if elementary and middle schools will remain closed (as I firmly believe they should do given the pandemic), we need to devise a workable solution that allows the parents to work and kids to learn. One such solution is educational family co-ops — families get together, form a quarantine bubble, and share responsibility for supervising all the kids in the co-op.

Whether you want to completely split from your school or use educational family co-ops together with the virtual instruction provided by your school district, the people you bubble with will be your close companions for the many months. Grouping with several other families provides kids with the friendships they lacked all summer and with the emotional support for everyone in the group. Since the people you would be bubbling with are not necessarily your close friends or relatives, you have to choose well not only for your kids but for yourself.

So what is the best way to pick families to join your educational family co-op? Here are six things you might want to consider.

1. Geographic Closeness

While family co-ops can bring together kids from across the city, it is much easier logistically to form one if all the families live in the same neighborhood. Like commuting to school, kids will need to be shuttled to and from the host parents each day. By narrowing the geographic range, you will eliminate a big source of friction — lateness in pick up and drop off. There are always emergencies, but if co-op members are routinely late delivering and picking up their kids, the disruption and bad feelings that this will cause can make the whole operation a bust.

This is not unique to family co-ops. There is a study of parents in Israel who were routinely tardy in picking their kids from daycare (always with good excuses). To combat the problem, the daycare started to charge parents late fees. But instead of curbing the problem, parents took this as permission to be late always! They saw the charge as good faith payment and treated the problem as one to be solved with money. This DOESN’T work for educational family co-ops. As soon as money starts to exchange hands between the parents, the promise of the enterprise breaks down, and essentially you would be running an unauthorized private school. This is NOT the point of this arraignment.

For those who would like to read about the problem of daycare economics, please consider reading the book by Nobel Prize-winning economist Daniel Kahneman: “Thinking Fast and Slow.” It’s a great book and I strongly recommend it.

2. Medical Conditions

We have been conditioned to keep our medical conditions secret or at least private. But if a kid has a peanut or a cat allergy, for example, the whole group needs to be made aware. More than that, since parents trade-off their homes as educational locations during the week, if one kid is allergic to dogs and one family owns a dog, it becomes a problem. So when you are starting up an educational family co-op, make sure that people are honest about any medical or other issues as they relate to the whole group. Medical secrets can kill the whole enterprise.

There are other problems: ADHD, autism spectrum, anxiety, potty training, etc. Be honest. Some conditions are actually less of a problem in a small family group setting even as they are very disruptive in the confines of the school classroom. But you can’t “sneak” ADHD into a family co-op without discussing it first (people will know with the first few hours anyway). That said, if you find a group of people you like, try it. Be kind. You might be pleasantly surprised at the outcome.

It would be a really good idea for everyone to get a clear COVID test prior to giving educational family co-ops a go. If you live in California, you will get your test results in just a few hours. It’s worth the peace of mind to get this done.

3. Size of the Group

Educational family co-ops work well if there are enough families to take charge of all kids one day a week. If you have fewer families, then the strain of dealing with all the kids multiple times a week outweighs the freedoms gained the other days. If there are more families, then the number of kids becomes too unmanageable. Try to keep the total number of kids under ten.

Families come in all shapes and sizes. But diversity is always an advantage. Consider every member of the educational family co-op, including children, as a contributing participant.

There are five families in the example shown here. Obviously the number of kids per family and the number of adults varies. How can the hours of instruction be divided in a fair way? Well, there are several solutions to this and it is something that you as a group need to negotiate before starting. Here are a few possibilities:

- Every family gets a day no matter how many children they have. On the first blush, this seems unfair — you have two kids, but I have only one! But all kids are different and their needs vary. Some kids are easy, and some kids are more difficult. You will know who is who soon enough. So it might be perfectly reasonable to just to say each family gets to supervise all kids one day a week and move on.

- Another way to approach bringing fairness into the division of labor is by assigning a day of supervision for each kid. This seems fair, but actually, one extra kid is not one extra day’s worth of effort. It’s all about the composition of the group.

- Instead of asking for a full extra day, you can also consider asking parents with two kids to hold longer “school days”. So a parent with only one kid might take everyone for 5 hours per day. But a parent of two kids might have an extended day of 7 hours.

- You might also consider the ages of the kids when figuring out the fairness equation. Younger kids have not been indoctrinated into how school works. For most children, it takes almost a year (a bit less or a bit more) to figure out how to sit still and pay attention for as long as the class is in session. Thus in many ways, younger kids might be more difficult to manage than older kids. So you can adjust hours based on the age of kids from each family.

The main thing is to keep things flexible and fair and to have regular discussions where grievances can be aired before they poison the whole arrangement. Remember, educational family co-ops are great BECAUSE they are flexible. When something doesn’t work for your group, you can change it as long as everyone agrees. And this is yet another reason to keep the co-op small — large groups never agree on everything.

4. Age of the Kids

There is a strong pressure to look only for families whose kids are all of an age. This is because we have been exposed to the factory model of education most of our lives. We are primed to see all six-year-olds placed into first grade. But this is mostly for the convenience of the school — it’s easier to pump the same content into all twenty (or thirty) kids if we assume them all to be the same (same year model). It costs less to disregard the differences in kids. But educational family co-ops should encourage to treat all the kids as individuals with individual abilities, interests, and levels of development. All six-year-olds are NOT the same.

There are a lot of advantages to having a mix of ages in your family co-op. First of all, this allows siblings to stay together and families don’t have to explore several other options for their children during this pandemic. Secondly, older kids are models for how students should behave and learn. The older kids should also take responsibility for teaching — teaching someone what you know reinforces that knowledge and makes more easily accessible and flexible. Having older kids in your group is not only easier on the supervising parent, it is good for the older kids, too. Right now, every year, kids learn the same things over and over again (perhaps at a more advanced level, but still there is a lot of repetition in the standard school curriculum). If instead of repetition, you allow older students to share and explain concepts that they had mastered previously to younger children, all benefit.

When Supermarket Science materials were taught in public schools, we set up the science buddies system. Fifth-graders adopted third graders; fourth-graders visited second graders; students in third grade made presentations for first-graders; and second-grade classes went to kindergartners for show and tell. Students not only had to learn something, but they also were required to create materials to teach what they knew to their younger peers, being careful to present information in a way that was appropriate to those kids. That required a lot of thinking and planning. Kids who participated in the science buddies program did better (anecdotally) on the end-of-school exams.

That said, you should aim for about two sets of kids in your group — those who would be attending lower and middle elementary school grades and those who are in fifth to seventh grades. Kids who are about to start high school will have online programs from their schools. The online curriculum works pretty well for older kids — they’ve already mastered what it means to be a student, not perfectly by any means, but we can expect older children to be internally motivated. Online only schools don’t work for younger kids.

Given the family examples above, educational family co-ops can easily accommodate kids who are working on the same materials at different levels of expectations. Supermarket Science materials are specifically set up to be used this way — depending on interest, motivation, and developmental level, all kids can engage with most of the materials on this site. This makes parent supervision doable. The sample families have kids in elementary and middle schools. This is a pretty good combination.

If you are working with your school district and your kids are assigned teachers and counselors, then having kids of slightly different ages is also a plus — you get “family visits” from ALL of the teachers. This is beneficial to the kids AND the schools. By having a spread in age, you should get a teacher visit every day of the week.

5. Duration

You might want to get a full workday out of this arrangement, but I wouldn’t recommend it. Start slow — 5-6 hours per day. This would make the task of supervising seven kids (as in our example) less scary. As parents (and kids) get more comfortable with the arraignment, you can scale up the hours. Even with just five hours per day, you will get 20 hours per week of supervised instruction. That’s more than you will get if the whole burden of minding your children is placed on your shoulders as schools go virtual this fall.

Kids will have a better time of it too — as fun as it is to stay at home with parents day in and out, hanging out with other kids is something to look forward to. And switching locations is a big plus too.

When you are negotiating how long the kids will spend each day with the supervising parent, you have to also negotiate what the kids will DO during that time. Educational family co-ops are not just fun time gatherings. The whole point is to get kids to learn what they are supposed to learn if they had spent that time at school. But unlike schools, educational family co-ops are far more flexible (or should be). You don’t have to adopt the approach of “if it’s 1:30, then we must do 45 minutes of math”. That kind of schedule is set up for the benefit of school administration. That said, there are certain activities and routines that help start and end the day.

Start with reading time: There are books that are appropriate for all the kids (just some are more difficult to read than others). Pick a story that is only read on Mondays, for example, and read it out loud to all the kids. Read for a half-hour or so — the younger kids will need a break after that. Then discuss what happened in the story. Are bad characters always bad? What makes someone bad? At this level of development, most kids see the world in black and white (kids don’t develop shades of morality until late into their middle school careers). Reading comprehension is an important skill that takes time to learn. You can ask older kids to summarize what happened in the story during the previous reading session. After a while, all kids can participate in creating verbal summaries — again, a very difficult skill to learn.

You can end the day by doing art projects. This way, you have some flexibility when parents arrive at slightly different times to pick up their children. Allow at least an hour for art. Also, make kids help with clean up (at the end of the day and between activities).

Do jumping jacks between all the activities — there is a lot of research that this type of coordinated physical moment helps with concentration. And it is also fun, can be done in tight places, and it engages kids physically.

Have a set time for lunch. Make sure that everyone has the same or nearly the same food. In such close small groups, any discrepancies in the types of food the kids eat might cause hurt feelings. You can even make lunches a way of learning about different cultures. Again, educational family co-ops give a lot of flexibility to families and kids to learn in a different way. By the time lunch is served, eaten, and cleaned up, it will be approximately 45 minutes. Thus almost 3 hours during the day will be spent reading, doing art projects, and eating (with breaks to shake off the willies). You will be left with two hours to take on a subject matter.

Not all parents are comfortable teaching all subject matters. But this is true only if you set up the notion that adults know everything best. Instead, if a parent becomes a participant in learning a new subject matter, not only will that parent have more fun, but kids will get to see what learning looks like when it is modeled by their parents. Supermarket Science materials are set up for everyone to learn something new. Seven kids and a parent make for an amazing dynamic collaborative learning group. This is a huge benefit of educational family co-ops. So build volcanos, explore how people live on volcano islands, etc. When we taught this at a public school, fourth-graders developed a plan of how to deal with San Francisco Zoo animals during a tsunami! Their plan was more thought-out and compassionate than what is on the books at the city hall.

Lots of Supermarket Science materials include the use of logic and the scientific method as well as math. The activities are not labeled “you will now do math!” Instead, kids learn naturally. This is yet another advantage.

If a particular parent has something unique to offer the group — language skills, computer programming expertise, musical education, art background, etc. — assign that person to teach those subjects to the group of kids while under his/her care. Take all the advantage of the talent pool you have to work with. And remember, you can always renegotiate.

If your school district insists that you make kids do worksheets, refuse. Google Classroom is horrible and should not be inflicted on kids (older or younger). If teachers or administrators need proof that your kids are learning, take photographs of children’s work and send them to schools as part of their educational portfolios. If your kids become better readers, writers, and listeners during this time, you are far ahead of the game. But your kids will learn so much more. Because reading about science IS reading! And writing about science IS writing! In real life, the subject matter is never isolated from context.

6. Politics

Yes, you will have to discuss politics, because we live in a highly politicized environment. But I’m not talking about the Red States versus Blue politics. All politics is local, and nothing is more local than educational family co-ops. What you need to discuss is the politics of pandemic. Everything seems to take on political overtones. Kids are worried about what’s going on around them, too. But no group of people agrees on every single point. To reduce conflict, stick to only those topics that are absolutely necessary to agree upon to run this co-op safely.

The reason you are probably considering starting your own educational family co-op right now is that either your school district is shut down OR you are not comfortable sending the kids to school due to fears of infection. Thus everyone in your group, including kids, needs to agree on what precautions they will take outside of your quarantine bubble. The kids in your co-op don’t have to wear masks while inside, but they should always wash their hands upon entering anyone’s house and always wear a mask outside.

But it’s not just the kids. Different parents face different risks. Some work at home and can mitigate their exposure to the virus well. Others have less control over their environment and safety. To make an effective quarantine bubble, every family must be on the same page when it comes to how seriously they are treating the risk of infection. Everyone needs to agree to get a flu vaccine this fall, for example. Co-ops need to negotiate what will happen if a kid becomes sick (not COVID, just a cold). Kids get sick all the time. They are sick, they are over it. Adults have a harder time of it. Discussing all of this ahead of time will minimize friction when someone gets sick (someone will get sick, it’s how life is).

The final bit of politics is money. I’ve already mentioned that buying time from a parent is a bad idea, but there are other economics that come in to play when starting up an educational family co-op. For starters, we all live in very different circumstances. It’s important that kids are aware of these differences (they always are, but they will be very explicit when they move from home to home during the week) and are respectful of them.

Some Quick Tips

With seven kids, you won’t need more than two foldout tables (the kind you can buy in any office supply store). During the day, kids switch out their sittings: older kids working with younger partners; older kids working together with their peers; etc. The advantage of folding tables is that it saves furniture — kids are hard on furniture. If an antique table gets damaged, there will be hard feelings. So remove that friction! Tables can be moved from place to place during the week — they are very light — or each set of households can get something that they can bring out. If you don’t want to use plastic tables, find a good sturdy tablecloth and be prepared for stains and scratches (we have the names of kids “carved” into out dinning-room table not on purpose, but because they pressed down on paper so hard that it left indents into the wood underneath).

If you use Supermarket Science materials, you will need a computer and a printer, but you won’t need a computer for each kid! All of these materials were made to be printed out so that the kids can work with paper. We found that younger kids do better working with paper than computer screens.

Some members of your group might have backyards, some won’t. Those that do can work with kids to plant seeds and learn about botany. Take advantage of what you have, of what’s doable.

Remember, ultimately flexibility is what will make this arrangement work. After all of you sign an educational family co-op agreement (this includes the kids) to give it a go, set a time period of trial. Give yourselves a month to see if this arraignment is working out for you. A month is enough for five families to experience all of the kids five times. Expect the first few times to be difficult — this arrangement will be new for everyone and thus confusing. But by the third time, everyone will have a sense of how this works and what role everyone is expected to play. But if after a month you find that there are bad fits, then it is time for an all families meeting. Layout the problems, see if everyone agrees, make decisions on how to move forward.

Everyone has a responsibility to make this work, even the youngest members. This is a social experiment and everyone gets to voice their opinions and suggestions, as long they are respectful and constructive.

Final Note — Hiring a Full Time Teacher for Your Co-op

I’ve heard people talking that a solution to school closures might be to hire a full-time teacher for your kids — a la governess, like in the “good old days.” Yes, I’m sure some families will do this. But here is the math. Expect the teacher to make around $150 per hour. At 6 hours per day and 5 days per week, this will cost $4,500 per week. You can divide this among several families, but the teacher will set the rules for how many children she/he is willing to take on. If you have 7 kids (as in our example above), the cost per kid will be $642.86 per kid per week. Perhaps given the costs of private schools this is just fine. But it is a lot of money. Educational family co-ops are for people who really can’t afford to lay out this much cash at this time.

There is also another problem with hiring a private teacher — that person becomes another vector for COVID. It is hard to stipulate that part of the job requirement is to never socialize outside of the kids that teacher is instructing. So you will just have to hope that the person you hire will be as careful as you are when it comes to pandemic risk management.

You might say that the same problem applies to the families in the co-op. Well, yes and no. The whole point is that this is a voluntary venture where everybody agrees to take on the same responsibility for everyone in the group. And the families form a quarantine bubble — there is no reason not to socialize outside of the “school” hours. The educational family co-op becomes a social relief valve for the whole family. Kids get to have friends they can play with face to face and adults will have a supportive circle of companions with similar views on pandemic and with the similar burden of raising kids. Just something to think about.