About Us

ZOMBies: Zones of Maximum Benefit

- May 8, 2020

- Posted by: Olga Werby

- Category: Supermarket Science Background

A Little Educational Background

We didn’t just throw these materials together. And I feel that it is always good to give a bit of educational background, when possible. So if this is of no interest, please skip to the next section which explains how to use our materials or start downloading materials.

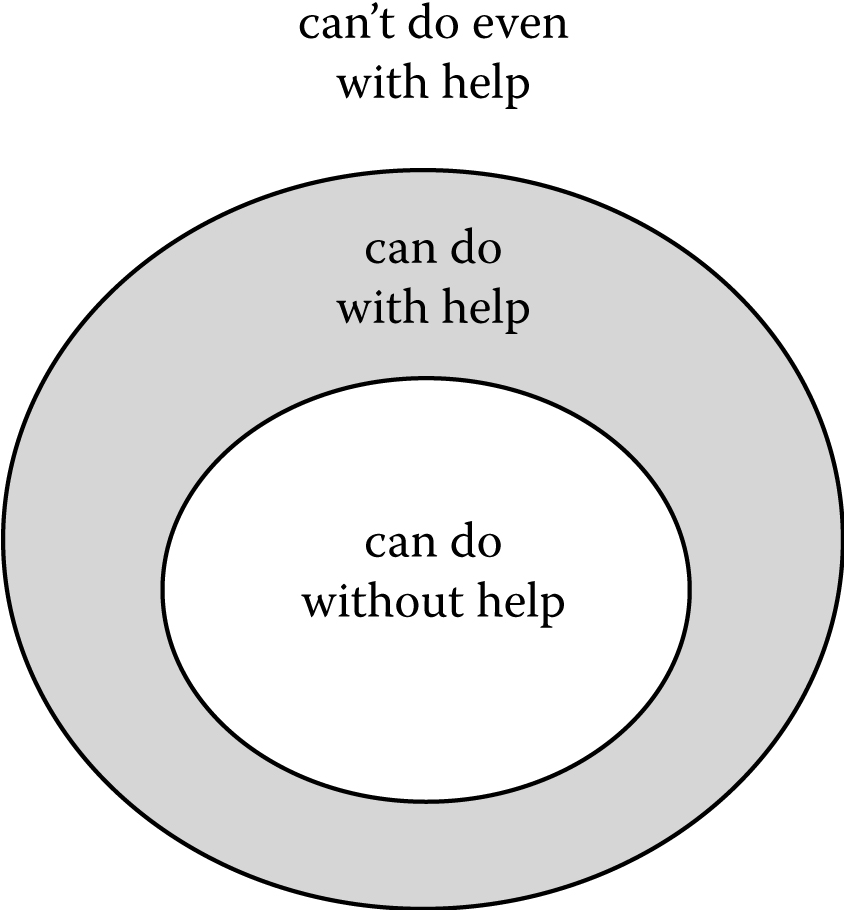

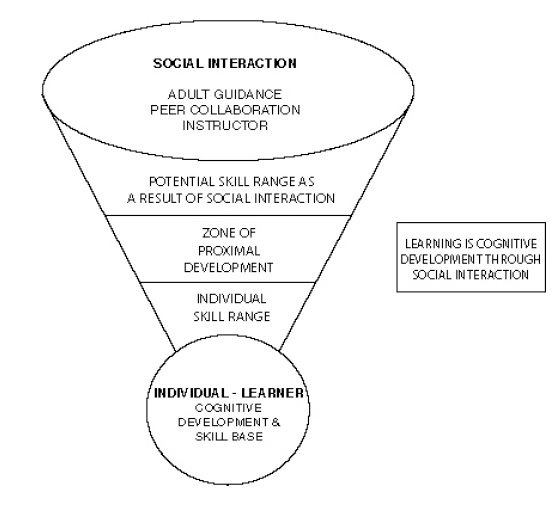

A well-designed science curriculum should serve as a bridge between what students already understand and know how to do and what they don’t know yet. That bridge exists within the Zone of Proximal Development (“ZPD”). ZPD is a concept introduced by a Russian psychologist, L. S. Vygotsky, in his theories on human knowledge acquisition shortly after the Russian Revolution. ZPD is the zone between what students know how to do on their own and what they can’t accomplish even with the help of a great teacher. It’s what a student can achieve with guided assistance. We now understand that all effective teaching efforts should be aimed at this zone. Efforts aimed beyond this zone, according to Vygotsky, will be ineffectual.

It is critical to know and understand the cognitive abilities of the students for which the instruction is designed. This allows the teacher or curriculum designer to determine her pupil’s ZPD. Once the teacher knows (or has a good guess) what a student is capable of doing in a particular domain with help, she can then develop supporting learning structures for a particular task. These support structures are called scaffolds and they are a key concept to effective instructional design. Scaffolds are cognitive support structures that aide students in accomplishing their goals in difficult situations.

Scaffolds are important, for they give a novice a chance to actually produce a product (e.g.: write a science paper or create a science fair project) or achieve a goal (e.g.: learn how to solve force problems or balance a chemical equation) that would otherwise not be possible. The sense of accomplishment felt by students during the early stages of learning in an unfamiliar domain can help them in their effort to master it.

It would be great to always be able to understand just what a student needs and to individualize the science curriculum to make those needs easier to meet. But in practice, it’s just not feasible. There are always budgetary issues, there never is enough time, and it’s hard to accommodate everyone all of the time. So instructional design is all about compromise: what is the best solution within our school’s means and doable within our classroom time frame? How can we try to accommodate the most number of students the maximum number of times?

The Zone of Maximum Benefit is my riff on the Zone of Proximal Development. While the instructional design solution must lie within the ZPD, its execution lies within the Zone of Maximum Benefit — do the best with what you got. In the context of teaching these ideas to fourth graders, I called it a learning “ZOMBie.” The kids talked about where their individual ZOMBies were all day. From that day forward, I referred to this concept as a ZOMBie.

But how does this work in actual practice? In a real classroom? In a busy public elementary or middle school? Supermarket Science Project was our answer to finding a ZOMBie in a public science curriculum. This is also the answer, we believe, for parents who are now finding themselves in the position of their children’s teachers for indefinite periods of time. Those parents and families that familiarize themselves with teaching tools and approaches will have better outcomes.

One last point of theory. Consider the problems of developing a good and effective curriculum. It would be great to have individualized learning materials that tightly fit the cognitive strengths and weaknesses of each student in a group (be that family with kids of different ages and abilities or classrooms full of kids coming from very diverse backgrounds). But that’s just not possible, even with computer-based learning — there are simply too many variables. However, we can design and develop educational materials in a wide variety of formats: graphical organizers and text-based outlines; visual illustrations and mathematical formulas; audiobooks, paperbacks, and movies; etc. The greater the variety of materials, the more likely some of them would fall within the preferred cognitive style of a particular child. This encapsulation of content can form the basis of scaffolded educational support.

Class over.